– One of my favorite themes to write about is the U.S. medical system vs. the socialized medical systems in use in many of the western democracies.

– In the last few days, I’ve had a personal and very real experience of how Socialized Medicine works here in New Zealand.

– I had a heart attack.

The suspect

The Event

– Last Thursday, I rode my bicycle into work. I’m not sure how far it is but I’m a fit and fast rider and it takes me 20+ minutes to make the journey through the city. When I finished work Thursday, I decided to see how quickly I could make the journey home so I rode hard all the way and arrived home in 15 minutes – a little out of breath but feeling fine.

– 20 minutes later, as I was sitting and talking to Colette as she prepared the evening meal, I began to feel quite odd. My upper spine, neck and jaw began to ache and I began to feel a bit queasy. I told her about this and went and lay down on the sofa to see if it would pass off. After a few minutes, it seemed like it was getting better so I got up and we ate the meal she’d prepared. But, as we got to the end of the meal, I began to feel poorly again and went and lay down on the sofa a second time. The symptoms were the same with the spine and the neck and jaws but getting stronger.

– After a few minutes, it came to an intensity where I thought, “I need to go into a medical center and see what this is all about.“, and I asked Colette to take me in.

– At this point, thinking back we should have called an ambulance, but I wasn’t thinking heart attack yet. I was just thinking that I was having some sort of weird event and should go find out what it was. It was around 6.15 PM when we took off.

– A 20 minute drive took us across the city to the 24 hour Emergency Clinic on Bealey Avenue.

– The medical authorities here in New Zealand prefer that most folks report to either their own doctor or the 24 Hour Clinic first, rather than going straight into the Public Hospital’s Emergency Room. But, just as in the U.S., many folks will take their kids with sniffles straight into the main hospital’s emergency room because it is free, rather than taking them into the 24 Hour Clinic, where there’s a charge to be paid.

– There are some very different pricing structures here in New Zealand for medical care compared to the U.S. but we’ll look into the details of all of that later.

– When I entered the clinic, just above the check-in desk was a sign that said, “If you are experiencing chest pain, please let the desk staff know and you will be seen immediately”. I did this and I was taken into a treatment room right away and was seen by a nurse who asked me a series of questions. In less than 10 minutes, a doctor was looking at me and an ECG was taken. It showed some abnormal descending strokes in the graph that are, apparently, indicative of a possible heart attack. The doctor decided that my symptoms and assessment results were serious enough to admit me to the hospital, and an ambulance was called to transport me.

– Meanwhile, the pain I’d been experiencing had moved from the jaw and upper spine to the more classic just-to-the-left of center chest. I never experienced the pain radiating down the left arm that I’ve heard is also a classic symptom of heart attack. But, by now I was beginning to believe that what I was experiencing was, indeed, a heart attack.

– And that was an amazing thought. I’ve always been fit, ate healthily and am a bit of an exercise aficionado. And, here in New Zealand, over the last year and a half, I’d lost a fair bit of weight (205 to 187 lb) which I didn’t think was too bad for a 5′ 11″ 63 year old male.

– But, be that as it may, the signs were getting stronger that I was having a heart attack as I lay there waiting for an ambulance to come. My pain was increasing and they gave me a morphine shot and I believe they also gave me something to prevent my blood from clotting. In five minutes, the pain was completely gone due to the shot. If I hadn’t experienced all that had gone before, it would have been hard to believe that anything was wrong with me. But, then the ambulance arrived to carry us to the hospital and it dispelled that notion.

– At every step, everyone was relaxed and yet entirely professional. I never felt like a number or like an object being shuffled through the ‘system’. Eye contact and human warmth were evident in each person I encountered along the way.

– Once at the hospital, I was wheeled directly into the emergency room and my chart from the 24 hour clinic was scrutinized and I was asked many questions – many of them repeats of earlier ones. Blood that had been drawn at the 24 hour clinic was sent with me in the ambulance. It was explained to me that by analyzing this blood, they would look for enzymes that would indicate if my heart muscle had sustained damage.

– If they didn’t find the enzymes, then I would be scheduled for treadmill tests to see what was wrong with me.

– But, if enzymes were found, then it would strongly indicate that I’d had a heart attack and I would be scheduled for an angiogram. An angiogram is an X-ray test that uses a special dye and camera to take pictures of the blood flow in an artery (such as those associated with the heart). Regardless of what the blood tests revealed, they were going to keep me for the night. A chest X-Ray was done and then I was taken to my room in Ward 12 (the coronary care unit). Four of the six beds were occupied when I arrived about 10.00 PM.

– I never felt any pain after the morphine shot and that evening in the ward was mellow. I read a book on my iPad and went to sleep about 11 PM.

Ward 12 - Cardiology

– The next morning, the blood test results came back. I’d definitely had a heart attack and there was an angiogram session in my future. But, now it got problematic as I’d checked in Thursday evening and Friday’s slots in the Cath Lab (where the angiograms are done) were booked up for the day. It was looking like I might be there for Friday and the weekend before I could get a slot in the Cath Lab. I was a bit anxious about that; imagining sitting in the bed or walking the ward for all those hours.

Home - Thursday and Friday night

– Colette came in and kept me company. And then, in a stroke of luck, a spot opened up in the Cath Lab which they told me about around mid-day. Yippie!

– True enough! And by 4 PM, I was back out again from the angiogram procedure to find Colette (who’d gone home) back waiting for me in my room.

– The angiogram procedure was relatively painless and I was awake the entire time. A small entrance to an artery in my right wrist was opened for access to my arterial system. I lay on my back with multiple large computer screens to my left and the doctors to my right. Directly over my chest was a computer-controlled movable X-Ray unit that was shifted around to view the heart from several directions. I was warned that there would be times when I’d have to turn my head, lest it take off my nose when it rotated.

– My right wrist ached as they worked on it, but not badly. They threaded a very long, thin catheter up my wrist artery and all they way through into the heart’s arteries.

– I watched what they were doing on the computer screens but, truthfully, I had no idea what I was seeing, though I watched with careful fascination. When the catheter reached my heart, they entered it into each set of arteries and injected an Iodine-based dye that showed the outline of the arteries on the computer screens via the X-Ray imaging.

Note the constriction

– I found out later that all my coronary arteries were in fairly good shape. They were open with fairly good flow, except the one that had caused the problem. And on that one, right at the junction of two arteries, it was badly constricted. See the image to the left where the arrow is pointing. Cardiologists use three levels to describe how badly closed an artery is; they say 50%, 75% or 99%. They said mine was 99%. This is why the heart muscle, which needs to be fed by these branches, was starving for Oxygen and dying. And this cell death is why the pain in my heart attack occurred.

– I asked the one of the doctors how these arteries get blocked off. He said they either do it slowly through the gradual accumulation of plaque along the walls or they do it suddenly when the harder surface of the inner wall of the artery splits and lets the softer material behind it protrude into the passageway.

– Given all the aerobic exercise I’ve done, I can’t believe this artery had been creeping slowly up to 99% blockage and I’d never noticed. I think there had to be sudden change at the end wherein a mostly blocked artery suddenly became almost totally blocked.

– They found the blocked area using the angiogram technique and then, once it was identified, they shifted to another technique called angioplasty. This is the technique of mechanically widening a narrowed or obstructed blood vessel using an empty and collapsed balloon on a guide wire, known as a balloon catheter. The balloon is passed into the narrowed area and then inflated to a fixed size. The balloon crushes the fatty deposits, opening up the blood vessel for improved flow, and then the balloon is deflated and withdrawn.

Stent in place

– After the area is expanded, a third technique is employed in which a “Stent” is placed in the newly widened area and allowed to expand to hold the arterial walls at that expansion.

– After this, the long, thin catheter is withdrawn and the arterial opening on the wrist is closed and the procedure is complete.

– I was back in my room by 4 PM, as I said, to find Colette waiting for me.

– They kept me Friday night for observation and during the night they checked my wrist and my blood pressure a number of times. Once again, I slept well. My wrist ached a bit from the trauma of the artery being opened but I had no other problems. I knew the stent was there but I couldn’t feel a thing. In fact, during the procedure itself, when the catheter was snaked all the way from my wrist into the arteries of my heart, I felt nothing. And, other than a small amount of local in my wrist, I was not anesthetized or sedated.

– Saturday morning came. 7 Am and the room lights came on and breakfast arrived soon afterward.

– Every hour or so, the nurse would come and relieve the pressure slightly on the device that was clamping the wound on my wrist. Arteries have a lot of pressure on them and to get one to seal and heal is not a trivial thing. After a number of pressure releases without blood spurting everywhere, it became obvious that it had closed correctly.

– Colette came in again (what a trooper she was through all of this!) and sat with me. We played some games on my iPad and waited for the cardiology doctor to come and talk with me and discharge me. Unfortunately, the doctor got tangled in an emergency situation in the morning so it was far into the afternoon before I was discharged. But, given all that had happened and how well it had all gone, I had no complaints about this.

The Costs

– Now, I want to talk about the costs of all of this. I.e., what I paid for these procedures here in New Zealand. These figures are in NZ dollars but you can translate them into US dollars by multiplying the New Zealand prices by .82 – which is roughly the current exchange rate.

Items:

1. Visit to 24 Hour Emergency Clinic – $100

2. Ambulance – $67

3. Hospital Room (2 nights) – $0

4. Angiogram Procedure – $0

5. Angioplasty Procedure – $0

6. Stent Procedure $0

7. Prescriptions for four drugs for three months – $22

– These prices are not exact but they are good ballpark figures and it all comes to about $187 NZD or about $153 USD.

– 19Jun2011 – I’m adjusting this section as the bills arrive. The 24 hour emergency bill came in and it was $100, not $150. Still waiting on the ambulance.

– 24Jun2011 – Ambulance bill came. $67 NZD. I’d estimated $50 NZD.

– 24Jun2011 – Also go a letter that I have (1) an ultrasound session appointment, (2) a physiotherapy session and (3) a follow on meeting with the doctor that put the stent in. My expectation is that because these are all part of the public health services, that I will not be charged for any of these. I’ll update this if that assumption is not true.

– I spent sometime this evening trying to come up with the prices for these procedures (Angiogram, Angioplasty and Stenting) in the US and it was a damn frustrating exercise – try it yourself.

– Try to find public, easily found figures for how much an Angiogram or an Angioplasty will cost you in a US hospital.

– But you’ll realize that there’s BIG money involved here. Because, when you go searching, you are going to find dozens and dozens of websites trying to sell you these procedures overseas.

– Consider: that for so many of these websites to be advertising with such competitive intensity, they must be able to still make a lot of money selling these procedures overseas for much less than they cost in the US – or they would not be in such a competitive advertising frenzy.

– All of this ought to be telling you something about the US medical costs and whether or not they are reasonable and proportional to the services delivered.

Summary

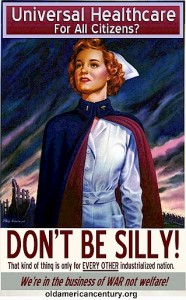

– When you are in the US , you will hear a lot about how wonderful the US medical system is and about how terrible the socialized medical systems in places like France, Canada and New Zealand are. They’ll tell you that you are very lucky to get the services you get, at the prices you get, in the US.

– It is an amazing pile of bull-droppings, is my opinion. The sad fact is that the American medical system has very largely been captured by the ‘everything- is-about-profits‘ corporate world and the American people are much the poorer for it.

– If you want to get into a detailed discussion point-by-point comparing the US system with the socialized systems, you will, I’m sure, be able to find a few points here and there in which the US system wins. But, on balance, the US system compares very badly.

– This has all been a near and dear subject to me over these last years and here’s a link that will take you through many of the things I’ve published previously on this Blog about the probems with US Healthcare and the US Medical System:

Click Here .

– If there’s a really sad bit to this story it is that all of this may have taken an option off the table for me. I love New Zealand but I always thought that someday, I might return to live out my twilight years in the US. I have some large doubts about that now. First, no one there would ever insure me (post heart attack) for anything I could afford – unless I get a lot more affluent than I am now. And, second, without insurance, I’d never be able to pay the bills if something did happen to me. And if I owned a house, a business, or some land in the US – whoop – they’d all be gone!

– You know, that’s just not right.

– Postscript: A friend, David D. wrote me about my thoughts here and pointed out something that I’d forgotten. And that is that when I turn 65, I will be eligible for the US’s Medicare System so I may still have US options on the table in terms of medical coverage and that nice. Thanks, Dave!

– Here in New Zealand, we all pay for healthcare through our taxes and we are all protected by each other’s payments.

– People say that taxes in countries with socialized medical systems are high. I don’t find them so. People with good jobs here will pay up to 33% of their wages as taxes. But, on the other hand, we don’t have to pay for medical insurance, automobile insurance or business liability insurance because a plague of lawyers hasn’t managed to take over the system here.

– People here expect that the system will take care of them if they get cancer or are in an automobile accident and they are incredulous when I tell them how the medical systems works in the US.

– Know that I am well, my friends. I’ve had a scare but in the big scheme of things, it was a relatively small heart attack. In three to six weeks, I’ll be resuming my life just as it was in terms of exercise.

– I like to report on how health care works in other countries outside of the U.S.   I do this mostly for my U.S. readers who are constantly besieged by propaganda from vested interests in the U.S. that are attempting to convince them that what they have in the U.S. is the best that can be had.

– I like to report on how health care works in other countries outside of the U.S.   I do this mostly for my U.S. readers who are constantly besieged by propaganda from vested interests in the U.S. that are attempting to convince them that what they have in the U.S. is the best that can be had.  who will fight to the death to prevent any serious cost cutting, and it’s why Obama and the Democrats in Congress have largely chosen to buy them off instead.

who will fight to the death to prevent any serious cost cutting, and it’s why Obama and the Democrats in Congress have largely chosen to buy them off instead.